Listen Back: The letters A-N

As we fly beyond the halfway point in our alphabetised list of album recommendations, here’s a round-up of every LP we’ve punted your way so far

Like an aurally fixated episode of Sesame Street, we’ve been compiling an A-Z of album recommendations for your listening pleasure. We’re more than halfway through the alphabet, so now seems as good a time as any to look back at our pop picks so far.

A

Many have overstated the extinction-level event facing the album. It’s true that teens are embracing playlists and algorithmic pop, but there’s something about a 40 minute-or-so collection from a songwriter that adds scope to music in a way that a single simply can’t. That’s the feeling you get from rapper Unknown T’s second album Adolescence (2021), a diaristic drill epic which hit at a time when the subgenre was a lightning rod for the right-wing press. Its lurching, murky production and insinuations about gang culture are best captured in ‘WW2’, a paranoid chronicle of trivial beefs showcasing the East Londoner’s lived-in rhymes.

From the loping threat of Homerton to the globe-trotting noise of MIA, whose debut Arular (2005) smashed into the charts with a mind-expanding mashup of electronica, rap, punk and glitchy beats that were entirely her own. The mid-2000s may be best known as the dawn of indie sleaze (and its bargain basement counterpart, landfill indie), but this British-Sri Lankan’s excitable bricolage is proof that there was vibrancy in the UK’s alternative scene away from guitar-battering lads in drainpipe jeans.

Other A listens: Anika by Anika (2010), American Dream by LCD Soundsystem (2017), Abbey Road by The Beatles (1969).

.jpg)

B

Ignore the whingers: guitar music isn’t dead and you don’t have to look far to find the good stuff. Case in point: Alvvays’ third album Blue Rev (2022) which resuscitates a sparkling jangly fuzz pop that had lain heaving since the 1990s. Molly Rankin’s vocals, both detached and effortlessly powerful, wrap around propulsive arrangements and scuzzy distortion (the handiwork of guitarist Alec O’Hanley) to form a pop missile that’s wholly immediate without losing its intricacy. It’s as sonically energising as a Smiths A-side and lyrically knotty on a par with The War On Drugs at their peak.

Teeming with ghostly synths seemingly beamed from another planet, Marianne Faithfull’s Broken English (1979) revels in pitting cold 1980s production against the formerly pitch-perfect singer’s cracked and rasping drawl; a decade of cigarettes, personal turmoil and heroin addiction had added creaks and crags to her every intonation. When she asks ‘what are you fighting for?’ during the title track, it sounds like a plea from a wounded veteran. History has cemented her place as one of rock’n’roll’s great survivors, but it was Broken English that confirmed Faithfull’s status as a consummate, forward-thinking artist.

Other B listens: Bandwagonesque by Teenage Fanclub (1991), Blind Faith by Blind Faith (1969), Bury Me At Makeout Creek by Mitski (2014).

.jpg)

C

Shoegaze rarely lets in rays of light, but Norwegian outfit Pom Poko could power a thousand solar panels with their second album Cheater (2021), which suffuses squalls of noise with excitable jazz, math rock and sugary note-acrobatics from vocalist Ragnhild Fangel Jamtveit. At every turn the technical skill is searing but it never threatens to overburden the tangible joy of a band letting loose. One for those that like their art rock with an explosive sensibility.

Sticking with bracing guitar music is Joy Division’s Closer (1980), a claustrophobic post-punk classic that bears the scars of economically depressed Salford. Unlike the leaps of flamboyance offered by their peers Bauhaus, there’s a single-minded focus here from Ian Curtis’ pain-stricken vocals, Peter Hook’s brooding basslines and drummer Stephen Morris’ coldly precise rhythms. Curtis died tragically two months prior to the album’s release, but Closer shows why Joy Division have remained a vital influence on countless other acts.

Other C listens: Candy Apple Grey by Hüsker Dü (1986), Copia by Eluvium (2007), Caprisongs by FKA Twigs (2022).

D

When cock-of-the-walk deck-botherers like Fred Again, Skrillex and Four Tet can headline Coachella with a passable mega mix, it’s a relief to see a DJ maintain the noble tradition of neutering their ego in favour of surprising beats. Canadian producer Jacques Greene fits that particular bill, his 2019 break-out Dawn Chorus offering a masterclass in depth, darkness and danceability. Favouring a hectic yet sombre palette, each track is a fevered collage of ideas, rabbiting forward without ever letting pace usurp form.

Revelling in dance of a very different kind is Björk’s Debut (1993), which eschewed The Sugarcubes’ oddball indie in pursuit of nightclub shimmers and house-inspired pianos, merging the Icelandic singer’s limber imaginative leaps with eclectic compositions that transcend genre. Its slavish adherence to four-four rhythms sounds quaint today, but album outliers like ‘Human Behaviour’, ‘Venus As A Boy’ and ‘The Anchor Song’ remain timeless, a precursor to the woozy otherworldliness that everyone's favourite multihyphenate would explore in later work.

Other D listens: Debutante by Femme (2016), Dusk by The The (1993), Dream On Dreamer by Shocking Blue (1973).

E

If William S Burroughs made psychedelic indie rock, it might sound like Spirit Of The Beehive’s 2021 outing Entertainment, Death, a cut-up experiment layering restless guitars over a shifting landscape of sonic abundance. Refusing to adhere to genre limitations, it veers minute-by-minute from glitchcore to found sound to synth-pop and everything in between. What could be indulgent is instead tightly strung, as wild in its ambition as it is accessible to a general audience.

Striking a more forbidding path in American experimentalism is Earth’s 73-minute masterpiece Earth 2 (1993). An impressionistic squall of gnarling guitars and distortion, the three songs comprising this ambient metal gem evoke primitivism in its most inchoate form, like our universe being sucked backwards into the gnashing jaws of the Big Bang. ‘Teeth Of Lions Rule The Divine’ is the stand-out track, scraping listeners across the hot coals of its fuzzy chords for 27 minutes before chewing them up on a wave of unanchorable feedback.

Other E listens: Electric Ladyland by The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1968), Eggsistentialism by The Lovely Eggs (2024), Entertainment! by Gang Of Four (1979).

F

‘Make way!’ exclaims Joe Casey at the start of Protomartyr’s Formal Growth In The Desert (2023). These Detroit noisemakers may be post-punk underdogs but here they behave like pugnacious champs, unleashing body blows on anyone who dares doubt their commitment to forbidding grooves. Casey remains the draw for his surreal writing, selling lines like ‘I was sucking on a rubber ear for your and my amusement’ with the conviction of a carnival barker. Hammering guitars launch his leftfield observations skyward, in a dynamic both hauntingly spare and wrapped in panoramic roars of distortion.

Also in the ‘down but far from out’ category is Nina Simone’s Fodder On My Wings (1982), which hit store shelves with a shoulder shrug from the public and critics alike. Soul, classical and calypso inflections are embedded in stories influenced by her time in Switzerland, Liberia and France. It’s as intricate and lyrically raw as anything from her imperial 1960s phase and, though flawed, standouts like ‘Alone Again Naturally’ or ‘Thandewye’ contain a bracing drama.

Other F listens: Finally We Are No One by Múm (2002), Four-Calendar Café by Cocteau Twins (1993), Fables Of The Reconstruction by REM (1985).

G

Welcoming listeners into a world inspired by the glaciers of Iceland, Gaister’s eponymously titled 2024 debut marks the first collaboration between songwriter Coby Sey, soprano Olivia Salvadori and Bo Ningen drummer Akihide Monna. Only a few synths, drums and a mixture of Japanese, Italian and English vocals are used to create a soundscape that’s frantic and ill at ease, its tectonic plates restlessly shifting between meditative calm and horror-movie terror. Sparse though it may be, Gaister’s self-imposed limitations made it one of the most consciousness-expanding releases of last year.

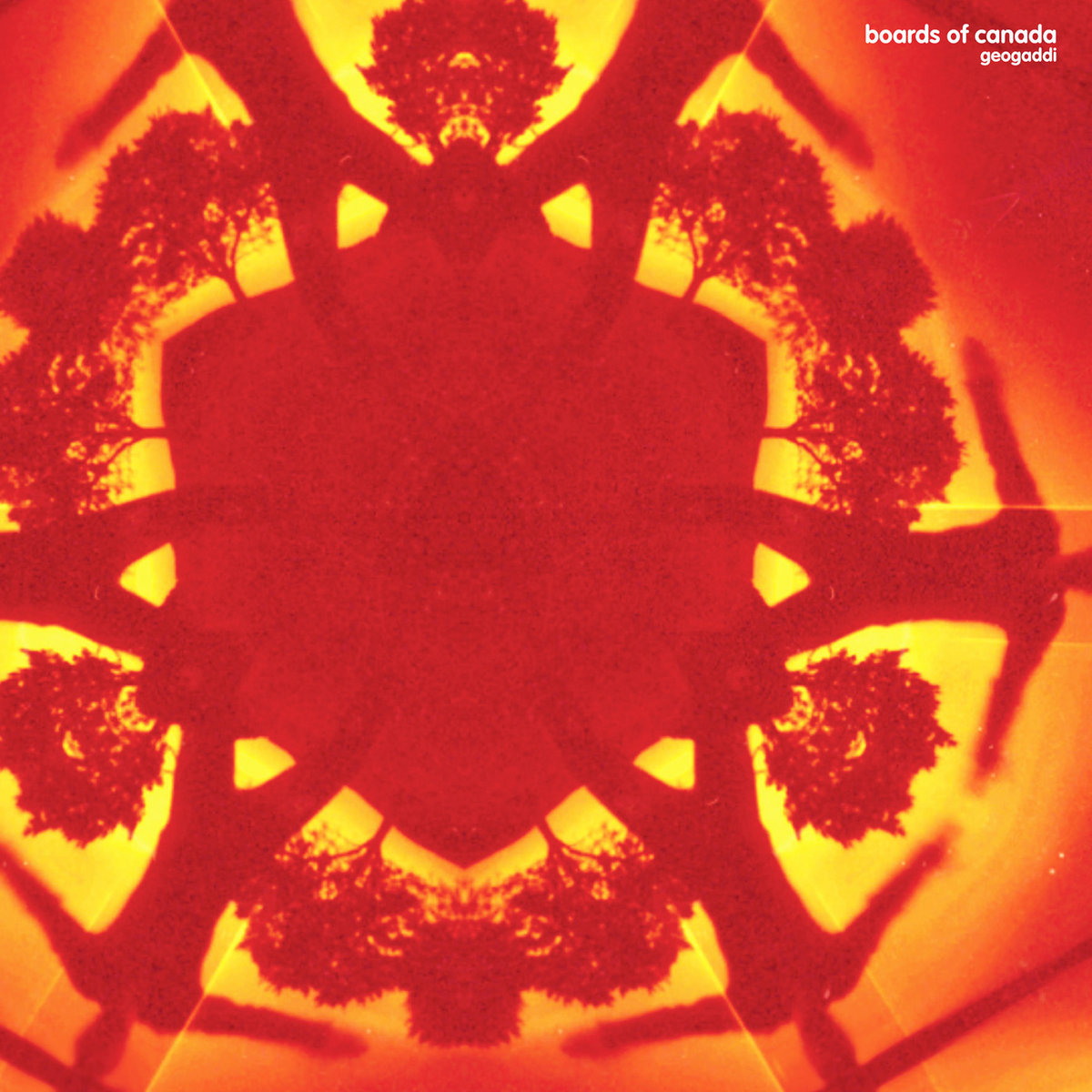

Eschewing an earthy approach in favour of distant synthetics is Boards Of Canada’s ambient masterpiece Geogaddi (2002). It ushered in a new digital age with haunted instruments trapped inside machines, voices vocoded out of all recognition, ultra-processed acoustic instruments, and drumbeats altered by the crunching numbers of computer programming. With a shadowy threat underpinning its chilly calm, the duo have claimed Geogaddi was a response to the September 11 attacks. To contemporary ears, its grim sense of subversion feels like a trek through the hinterlands of the internet’s early untamed era.

Other G listens: Grush by μ-Ziq (2024), Game Theory by The Roots (2006), Gorilla by The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band (1967).

H

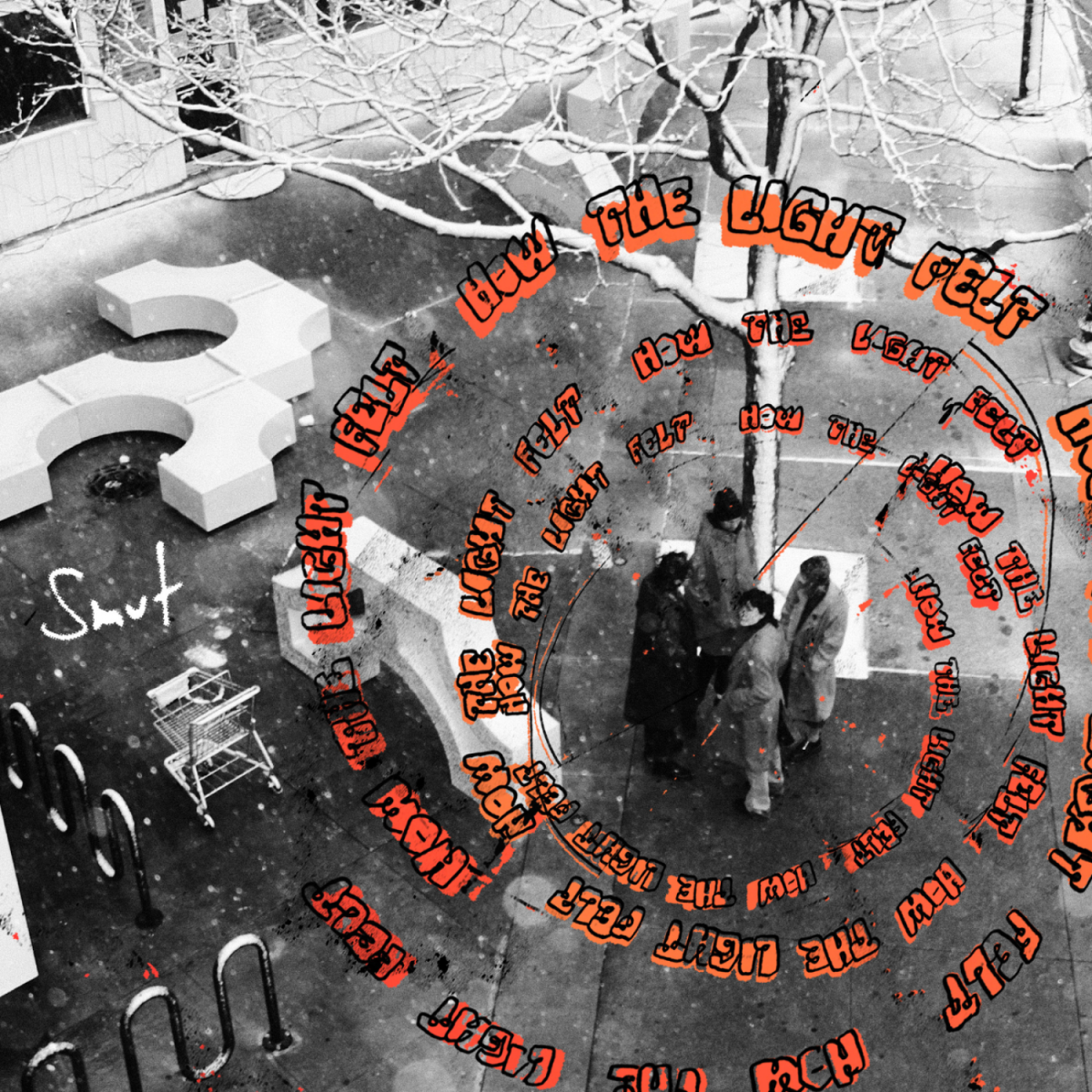

The dream-pop sparkle of Smut’s How The Light Felt (2022) gestures towards one of the lesser-walked paths of 90s revivalism, with hooks and a wistful energy that crib lovingly from Swervedriver and Lush. It’s a trek into throwback territory that never uses its reference points as a crutch, not least because tracks such as ‘After Silver Leaves’ and ‘Morningstar’ exhibit a craft equal to their antecedents. In another dimension (or perhaps simply another era), this would have been a chart-stormer.

Filed at the back of Smut’s rolodex of influences is Bark Psychosis’ debut Hex (1994), a maudlin post-rocker lingering in the space between sleep and wakefulness. Each arrangement is a series of left turns, unfurling with a wild array of instrumental flourishes before retreating into sparse bass lines. Disaffection in the 90s was popularised by the roguishness of Pavement or Slint, but this southern English quartet carry a greater weight on their shoulders, every muttered vocal and catatonic time signature an exhalation of unwavering apathy.

Other H listens: Here Come The Warm Jets by Brian Eno (1974), Hats by The Blue Nile (1989), Have One On Me by Joanna Newsom (2010).

I

In the hit-averse hinterland of experimental music, there are two categories: the forbiddingly difficult and the surprisingly seductive. L’Rain (nom de plume of American songwriter Taja Cheek) falls into the latter category, and I Killed Your Dog (2023) is maybe her most accessible work yet. The Brooklynite’s soulful tones (imagine Solange without the plaintive angst) combine with a woozy obfuscation of funk, indie, syncopated drums and swirling electronics to create a barrelling liminal space between freewheeling wildness and controlled chaos.

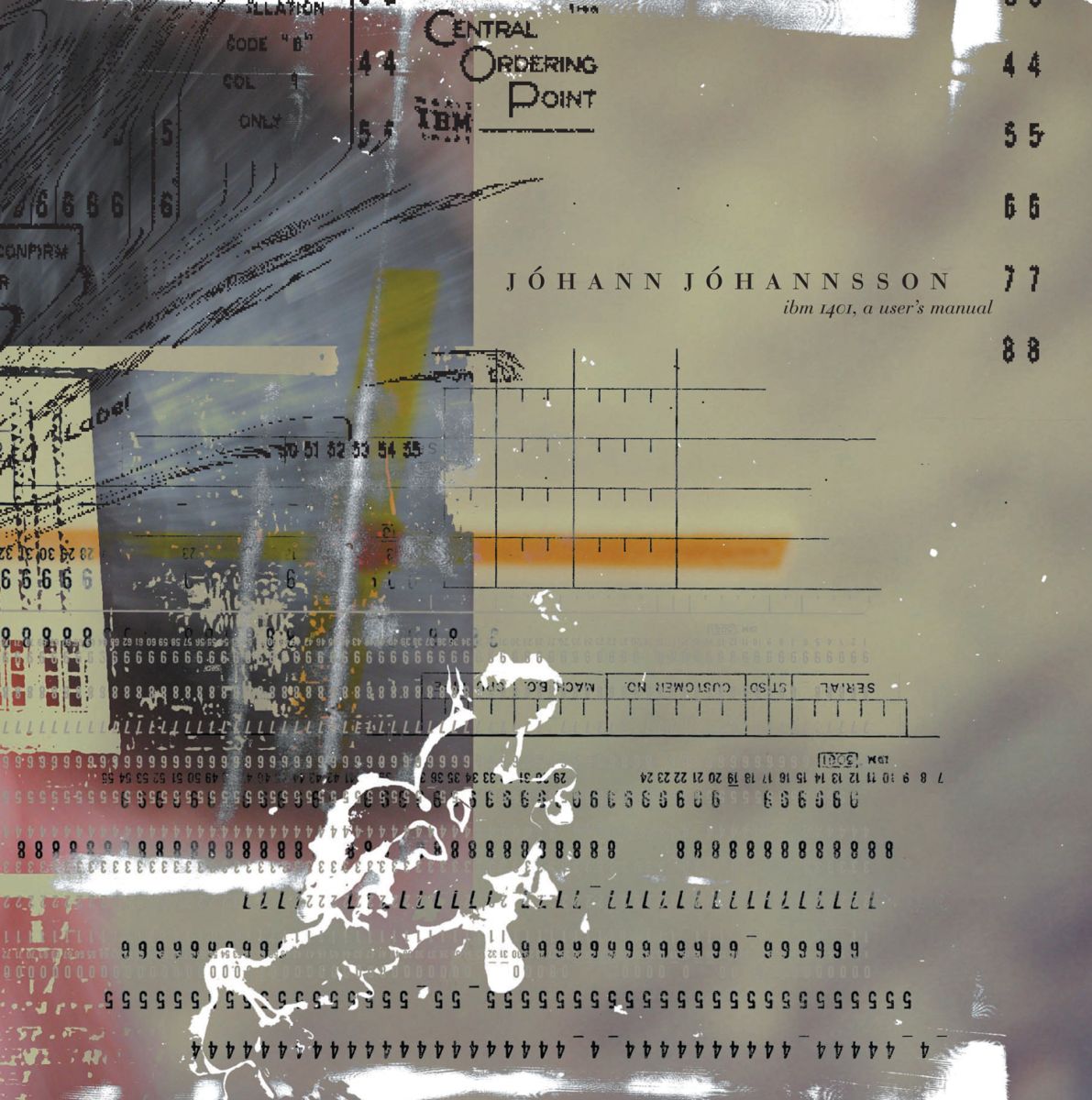

Steering the avant-garde towards a more uncomplicatedly beautiful direction is the late Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson’s IBM 1401, A User’s Manual (2006). Here temperatures clash with the spark of iron pyrites smashing together, the sterile coldness of the information age (including a narrator drily reciting a printer assembly instruction manual on ‘Part 2/IBM 1403 Printer’) interloping with the warming passion of the City Of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra in full flow. Plenty of musicians have merged these opposites, but few have achieved such soaring beauty.

Other I listens: I Can Hear Your Heart by Aidan John Moffat (2004), Illadelph Halflife by The Roots (1996), I Am Kurious Oranj by The Fall (1988).

J

An acoustic record from Bill Orcutt is a very rare and special thing, and Jump On It (2023) proves why. His languid playing on these improvisational numbers steers listeners into a warm bath while handing them a strong shot of whisky, sparking conversations in the mind without ever insisting on a topic. A choppy roughness tends to lie at the heart of Orcutt’s electric work, but here he resists his contrarian impulses to render serene and intimate hymnals on the history of the guitar.

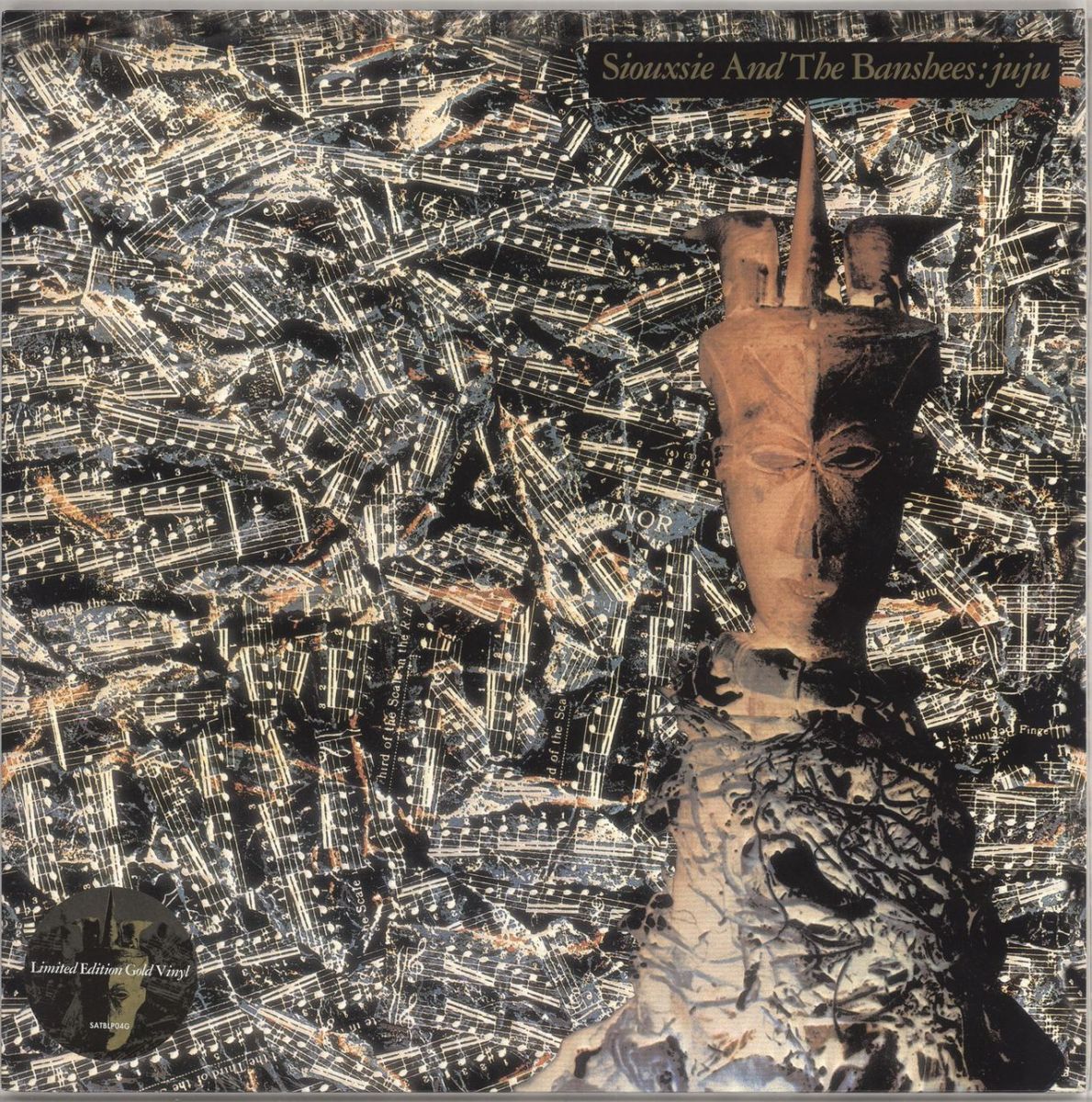

From the frantic snares of ‘Spellbound’ to the goth-stomp psychedelia of ‘Voodoo Dolly’, a firework energy flashes through Siouxsie And The Banshees’ Juju (1981), their fourth and finest marriage of Siouxsie Sioux’s baroque howl and John McGeoch’s fidgety guitar. Theatrical without descending into camp, technical without eschewing passion, poetic without shirking from a singalong chorus: there’s a good reason that this is viewed as the defining album of post-rock’s first wave.

Other J listens: Jeopardy by The Sound (1980), Jubilee by Japanese Breakfast (2021), Just As I Am by Bill Withers (1971).

K

Afro-maximalism is the genre favoured by American folk singer Anjimile in The King (2023), which turns the light pluck of an acoustic guitar into an unrelenting display of acrimony. Floating vocal harmonies flutter in the background of its strongest songs, buttressing Anjimile’s rich vocals that flit between regretful to pained. Its folky undercurrent should be calming, but their piquant for screeching guitars and violent crashes of noise make the experience as threatening as a hammer to the temple.

Also burrowing into drone noises and distorted vocals is Radiohead’s Kid A (2000), a fin de siècle masterpiece which draws inspiration from the glitchy ambient of Boards Of Canada to create a Moog-molesting underground album on a major-label budget. Crowd-pleasers are in strong supply throughout, from the balls-to-the-wall bassline of ‘The National Anthem’ to the ethereal melody of ‘How To Disappear Completely’, but this jailbreak from stadium rock baffled critics at the time.

Other K listens: Kind Of Blue by Miles Davis (1959), The Kreuzberg Press by Man Without Machines (2013), Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me by The Cure (1987).

L

There are many sounds in LEWISPYBEY (2024), an experimental collaboration between Edvard Graham Lewis and Mark Spybey, and most of them are laced with threat. There are ominous gloops like a killer traipsing through swampland; digital interference that an EMP device might make if it detonated in your brain; long drones that recall an ancient chant looping in some forgotten monastery. Yet somehow this forbidding electronica is unafraid of hooks that, while not quite danceable, tether its wild melange, gesturing towards horror while never forgetting to have a good time.

Paul McCartney’s avant-garde impulses are rarely championed, but on Liverpool Sound Collage (2000) they’re pushed to their limit. Challenged by the artist Peter Blake to create a soundtrack for his latest exhibition at Tate Liverpool, the former moptop sculpted a musique concrète patchwork of cut-up beats and archival clips (including background chatter sourced from Beatles recording sessions). It’s diverting enough to imagine a different life for McCartney in the 21st century, one spent tinkering on a laptop instead of strumming a guitar.

Other L listens: Lives Outgrown by Beth Gibbons (2024), Landwerk by Nathan Salsburg (2020), Loveless by My Bloody Valentine (1991).

M

Distilling the underground club scene to its most hectic elements, London-based Djrum created a wild, inordinately stressful experience with Meaning’s Edge (2024). Tempos shift with an athletic grace, while its unfathomably complex layering creates a mathematically precise concatenation of pinballing emotions. Moments of flutes and ambient offer a brief caesura before the ricocheting patterns of chaos begin again.

Hitting dancefloors of a very different sort is Madonna’s Music (2000). Madge had long since given up her role as a trendsetter by this point, instead acting as a conduit between mainstream audiences and hipster trends. Here, she effortlessly adds pop textures to trip hop with the air of a sophisticate sharing their newfound passion rather than a careerist clutching at relevancy (not something that can be said of her later output). Sure, it’s patchy (‘American Pie’ is to be endured more than enjoyed) but ‘What It Feels Like For A Girl’ and ‘Runaway Lover’ are top-tier entries from the end of the voguer-in-chief’s reign.

Other M listens: Mug Museum by Cate Le Bon (2012), Manuela by Manuela (2017), Maggot Brain by Funkadelic (1971).

N

Mythic and sprawling, Arooj Aftab’s Night Reign (2024) is awash with sleepy textures of crepuscular hypnagogia. With the Urdu language poet Mah Laqa Bai as a point of inspiration, its epic knottiness isn’t afraid to melt into a slinky Pakistani folk on ‘Autumn Leaves’ or ‘Last Night Reprise’, communicating an ineluctable landscape of woozy majesty. Apparently its creative process was fraught with indecision and compromise as Aftab toyed with the notion of making a full-blown concept album. You’d never guess as this is one of the most confident releases of the past few years.

Ever wondered what The Slits would sound like if they hailed from China? Probably not, but Beijing-based Hang On The Box answered that question with their 2007 shonky punk powerhouse, No More Nice Girls, a lo-fi outing that embraces the limitations of its production. As China’s first all-female punk act, there’s a quiet revolution happening on every Hang On The Box record, backed up by a proudly ragged approach to craft.

Other N listens: No One Can Ever Know by The Twilight Sad (2012), New Skin For The Old Ceremony by Leonard Cohen (1974), Neu! by Neu! (1972).